Jordan Casteel

Returning the Gaze

February 2, 2019 – August 18, 2019

Curated by Rebecca R. Hart

Installation View of “Returning the Gaze,” courtesy Casey Kaplan Gallery.

One normally expects to do the looking in a museum or gallery space, not to be the thing looked at. “Returning the Gaze,” first major museum show of painter Jordan Casteel, flips this idea on its head. Upon entering the exhibition space at the Denver Art Museum, visitors are first met with three sets of eyes. The faces within Benyam, 2018, look down: a woman in an apron sits on a barstool; two men – one fedora-wearing, one with a “QUEENS” baseball cap – lean over the counter. Behind them a simple shelf with some cups, and some paintings on the wall, set the scene as a little café. In this painting, and most of the others throughout the exhibition, Casteel has turned the subject into the viewer. However, this act of looking back is not aggressive, but rather open and inquisitive.

Casteel seems to challenge that long-held piece of parental advice to not talk to strangers. Not only can one imagine going up to any of these three figures at the counter in Benyam, but Casteel in fact talks to these once-strangers to paint their portraits. Though she grew up in Denver (making this debut particularly exciting to her childhood community), the artist is now based in New York City. For the paintings in “Returning the Gaze,” she walked around Harlem and looked for interesting people to talk to, to photograph, and then to paint. Casteel encourages this openness her viewers as well – the call to be “an empathetic observer” is the charge of the show as a whole (Casteel, wall text).

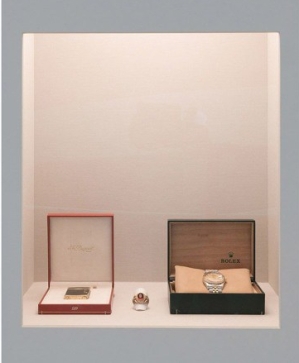

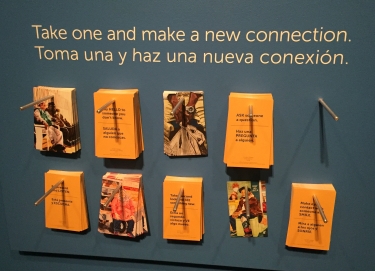

The Denver Art Museum has taken this encouragement of empathy and community to a literal level. At the entrance to the exhibition is a wall featuring hanging activity cards. One side of each card features a detail of one of the paintings in the show; the other has a command for how to engage with the space and/ or the work. These are such actions as “Be present and LISTEN,” and “Make eye contact with someone and SMILE” – written in both English and Spanish.

Image courtesy of author

Combined, Benyam and the cards set the tone: this is no time to stand back and passively look at some “nice” paintings. And, indeed, on the day that this visitor attended, the space was alive. Never have I seen such a packed gallery at the DAM, nor with such a diverse audience – people of all races, ages, and abilities were present, looking back at the faces and relationships that gave them something with which to identify.

After studying art history in college, Casteel decided that she wanted to create work that would feature people of color (especially black men) in order to reclaim and and humanize those historically objectified bodies. Using bold colors, soft blending, and organic lines – plus, of course, that powerful gaze – Casteel elegantly and effectively returns humanity to her subjects. In the February 2 “Teen Q+A with Jordan Casteel,” the artist said that making her subjects break the fourth wall and look directly out from the canvas allows them to “retain their power out in the world,” beyond the walls of the artist’s studio.

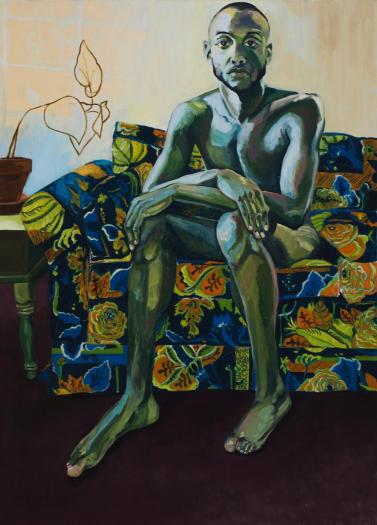

The exhibition is divided into five parts: Brotherhood, Harlem, Community, Invisible/ Visible, and Subway Paintings. Brotherhood, the first section, focuses on portraits of Casteel’s family, including a beautiful painting of her mother (Mom, 2013) – the only one in the show where the subject’s eyes are both closed and turned away from the viewer. Harlem focuses on some of those community members that caught Casteel’s eye – a trio of stylish black men sitting on a stoop (Cowboy E, Sean Cross, and Og Jabar, 2017); a couple bundled up, holding hands and sitting by an elaborate fence in rendered in light-salmon hues (Yvonne and James, 2017). Community includes works that are focused on businesses in Harlem, like Casteel’s favorite restaurant, or a hair salon (Amina, 2017).I found Invisible/ Visible and Subway Paintings to be the crux of the show: they fit her community mission, and were the most visually powerful. In Invisible/ Visible, Casteel depicts nude black men – often friends and colleagues from her Yale years. In Ato, 2014, the title subject sits curled up in a chair, arms wrapped around his knees, pulled to his chest. Ato’s head tips to his left, resting on his knees. This almost-flirtatious pose somehow remains far from sexy – in his curled position, the man portrays a sense of childlike innocence. An orange curtain flutters behind him, his orange chair sags, his orange-undertoned skin radiates light. It is a magnetic painting that seems to capture a warm spirit rather than a seduction. Other men are portrayed in brighter colors. Jiréh (2014) is green. He sits on a tropically-patterned couch, arms hung casually over his knees, wrists crossed, long fingers dangling. He sits comfortably in his home – were it but for the nudity, a viewer might think she was sitting on an equally bright couch across from him, carrying on a conversation. In Isolde Brielmaier’s essay (“Hitting the Pavement: Jordan Casteel’s Street Portraits”) for the slim yet beautiful catalog that accompanies the show, she describes this quality as “a feeling of comfort and familiarity” – something that merges public and private in Casteel’s art (Brielmaier, 44).

Jordan Casteel. Jireh. 2014. Image from https://www.artandobject.com/shorts/returning-gaze-portraiture-encourages-empathy

Jiréh had a special label for the exhibition. In it, Jiréh describes meeting Casteel at Yale, and says that “Jordan’s paintings ‘saw’ something in us [black men at Yale], and we were able to see something in each other that was and remains deeply meaningful.” Unfortunately, this was one of only three such subject labels in the exhibition. In a show that was curated so well – not crowding the works, flowing well from section to the next, clearly demarcated categories, concise labels – this lack of “story labels” was my biggest disappointment. Though the returned gaze of each subject was meaningful in itself, I believe that a few more opportunities to give those titular figures a voice would have made the show even stronger.

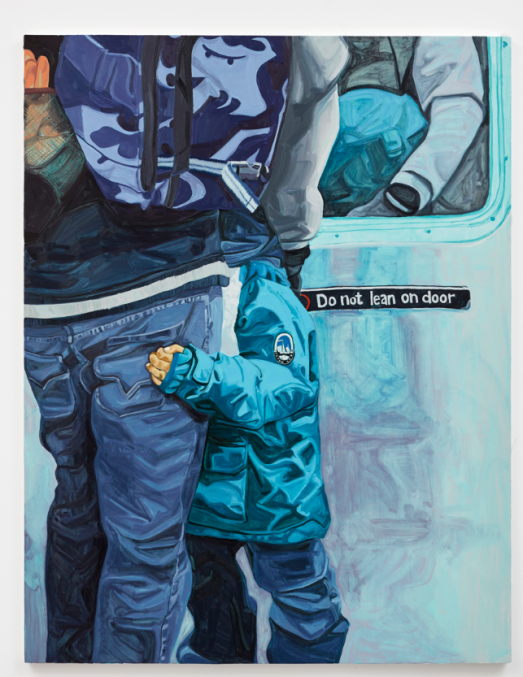

The Subway Paintings were the brilliant conclusion of the exhibition. While to this point the work had been about making a connection through direct looking and looking-back, this final section of the exhibition shifted that: each of these smaller paintings was anonymous, faceless, and based on sly photographs that Casteel had taken on the subway. As a final moment of the show it was poetic: after all of the eye-contact and direct engagement, here was a moment to think about connection in a new way. In the background one could hear Casteel speaking about her practice from a video playing in the corner, but other than that, this area was much quieter than the rest of the exhibition. Many of the Subway Paintings are of hands: hands holding phones, shopping bags, draped over laps. Hands are, of course, just as unique as faces, though perhaps not so individually recognizable. What does it mean to gaze on an individual, these paintings seem to ask, when the receiver of the look has no idea, and when they are unable to look back? This is the conundrum of many historic portraits, and is the dynamic Casteel tackles head-on.

Subway Paintings installation view at DAM, image from author.

This canon-busting question swam in my mind as I turned and took in one of the last paintings of the show. A shock of blue met my eye at first glance of Lean, 2018. Though not physically the largest painting in “Returning the Gaze,” this one felt monumental in a different way than many of the other works. In it, a boy clings to his father’s leg on the subway. Dad’s arm tucks the boy’s head against him. The child’s back reflects in the subway window, below which a sign reads “Do not lean on door.” Everything is blue and white and purple – save for the flash of an orange work glove in the man’s backpack pocket. Clearly demarcated areas of color in the two figures contrast the blended style of the subway door. The boy’s fingers curl around the man’s back pocket. The entirety of their bodies is not shown: the man is cut off from his shoulders up, both are cut from knees down. Looking at the intricacies of the painting, I could practically feel the denim against those tiny fingers, and imagine the rattle of the floor against my feet. There was something so visceral in the work – despite its facelessness. The anonymity seemed to make it universal: you, too, have leaned on someone. Lean shifts the kind of gaze of the first painting, Benyam; it reminded me of the show’s call for empathy, or of the card in my hand asking me to be present, or to say hello, or to slow down. Cumulatively, this end and its lack of eye contact reminded me of my own face among many, and asked me to look around, and forge my own Casteel-inspired connection.

Jordan Casteel. Lean. 2018. Image courtesy Casey Kaplan Gallery.