In an exhibition whose title highlights breath, I found myself drawn to the concept of touch. Not simply touch as a sense, but as a concept, because of the implications of such a thing: the pressure of stone on wood, the force of a pen tip scarring paper, the impact one life has on another.

Danh Vo (born in Vietnam and now working between Berlin and Mexico City) appropriates, alters, and re-purposes found materials and objects to create new meaning, often merging the personal and the political with a deft hand. His artwork, while on the surface sparse and approachable, sits with you the more you sit with it.

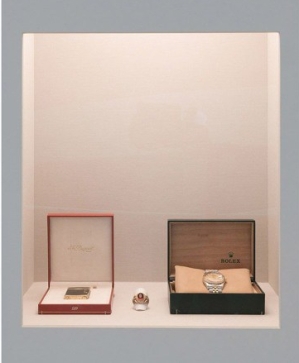

With a light touch, a case containing a watch, lighter, and ring becomes a meditation on perceived masculinity, ownership, and inheritance. These objects – once belonging to Vo’s father – are at once minuscule and monolithic. Touch: a metal clock against soft skin.

The Unabomber’s typewriter is dethroned, sitting innocently on the floor, small and unassuming – non-mythical without a label shoving away the subtlety. Fingerprints on letter keys, one tapping against the other.

Further along, Beauty Queen is unassuming on the floor – a 400 year old wooden torso of crucified Jesus, separated from the rest of the body, placed in a box to the perfect fit. Above, dismembered pieces of a copy Statue of Liberty (We The People) strewn across the floor – a thumb as big as a child; the curve of a wrist large enough that I could tuck myself into it; a sheen on the horizon becoming a shine against the white of a gallery floor. People step among the story of Vo’s connection to immigration, and the repeating motif of “an iconoclastic approach” (as described in one of the exhibition’s labels); these ideas are simultaneously evident and nuanced – like the light reflecting off of the installation.

Vo’s work is dense, but it never feels too heavy.

In an exhibition filled with mighty materials, stone, wood, and metal aged to earthy musty richness and worn nostalgic metallics, I was most drawn to the delicacy and intimacy of paper.

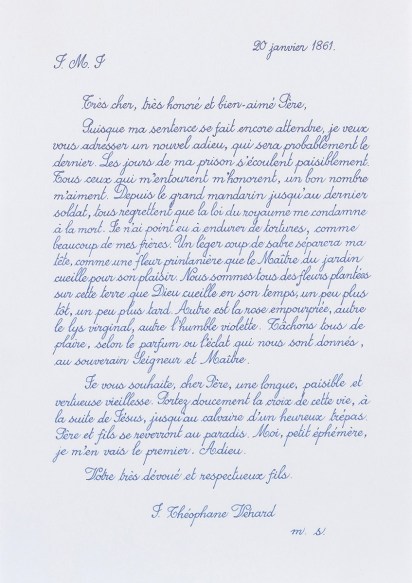

2.2.1861 – one in an ongoing series of letters – is understated among the range of materials and physical dimensionality of the other works in the exhibition. Where other objects are gold and brown and slick and woody, this one is smooth and quiet. Phung Vo, Danh Vo’s father, has copied this letter numerous times over the past nine years. Each time, it is the same – a correspondence from Théophane Vénard to his father before his decapitation in 1861; each time it is different, featuring nuances of the hand at work – a letter with a slightly steeper slant, a bolder dot where pen first met paper before skimming off into a looping letter turning word. The letter is in French – a language that Phung does not know – and he copies it in a beautiful, swooping calligraphic script that he has mastered. He can touch and sculpt the words, but cannot feel the language. The letter echoes – father to son/ father to son, copy/ copy/ copy/ copy, ink flowing from pen tip, border crossings between writer and artist and receiver.

2.2.1861 (2009- ongoing)

When I returned home from the exhibition, I wrote a postcard to my family, not thinking about my purple marker or the crispness of my penmanship – and not writing about an impending decapitation. As I wrote, my pen made little scratching noises against the fiber of the paper, pressing ink and color against the substrate.

To emboss is to stamp or carve onto a surface so that the pressed portions become raised. If you look at it that way, while of course the letter coincides with Vo’s conceptual oeuvre, it also feels like a tactile companion to the other works. If you were to draw that link in the air between each artwork, what would it feel like to touch?

Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away is on view at the Guggenheim in New York City through May 9, 2018.